Fragment of Alexei Chernigin's interview for the French magazine «Pratique des arts».

I think the most interesting and the most difficult part of my profession is learning to react to the world around me in my own way, in my own way. After all, people often just don’t see anything around them. Or rather, they see, but they do not feel with their eyes. Yes, we see things around us, we don’t bump into poles as we walk down the street, we get into doorways, but all things to us are just symbols, conventions, like in a computer game. They don’t interest us in themselves. It takes time, and in our accelerating world we are starved for it, we are always in a hurry, perceiving the world as a clip, a kaleidoscope of vivid frames. We are chasing after new impressions, taking countless pictures, adding millions of new frames to the web every second. And it is only by slowing down this crazy rhythm, by dissolving into the feeling of the experienced moment, that you can try to start seeing in a different way. In doing so, you forget about yourself, or rather begin to feel yourself through your surroundings. You have to get into resonance with the surroundings, to feel their pulsation inside. Brodsky describes this state beautifully in his essay on Venice: “The eye in this city becomes independent, like a tear. It is not detached from the body, but completely submits it to itself. A little time, and the body already considers itself only a vehicle of the eye, a kind of submarine for its open periscope. Sometimes such readjustment takes a long time, sometimes it does not work at all. But when this short circuit occurs, you are immersed in a magical state of thick, viscous enjoyment of the fullness of life. This is the beginning of creativity.

In many of my canvases I explore the theme of speed, movement, the relationship between man and the city. We live in the rhythm of the city, submit to its chaotic movement, dissolve in it. But sometimes I want to stop, to step out of the flow, to look at this multidirectional movement from the side. In general, speed, it seems to me, is a central concept in painting. Without it painting is dead. We find this idea in Andrew Wyeth, the greatest American artist: “The main thing is the inner movement in the picture. The painting represents space, the inner speed brings the category of time into the painting. And together space and time form life. And this internal velocity is different in every picture. It can be subtle, like the morning breeze, or the slow movement of dust particles in a beam of light, as in Wyeth’s own work. But that inner speed is there all the same.

Each new work is a new story. There are times when a work is written in a day, times when it takes years to be born. I love it when a work comes out all at once, but that’s rarely the case, often it’s just technologically unfeasible. But we are considering only the process of painting, but there is an underwater part – the development of the concept, the search for composition, sketches, studies. A painting isn’t born suddenly. It’s always a layer of life, the idea appears as a light breath of wind, as the 25th frame, flashed and got stuck somewhere deep and deep. It does not reveal itself for a while, until a chance association superimposes itself on it, causing a completely new reading. Then it begins to spin out, like a wheel, getting more and more images, and gradually forms into an internal picture, which tears out, doesn’t give you peace.

I am convinced that inspiration does not dawn on lazybones, only systematic work, a state of constant involvement in the process can give results. One of Dali’s principles: Artist, draw! It’s simple and brilliant, it’s a recipe for all times.

I once saw an interview with Mikhail Shemyakin in which he spoke frankly and simply about his working methods. The master talked about how he tried to catch every new potentially interesting idea, meticulously recording it in a separate folder and placing it in his “library of ideas. At first it seemed to me that this approach smacks of mothballs and accounting. But gradually I began to understand that in order to move to a new level just need to understand its “pile of ideas,” to systematize it and then follow the advice Shemyakin, carefully treating their insights.

At first some image or fragmentary impression, a phrase from a conversation or simply a word appears in my folder. Gradually the folder is filled with new images that directly or indirectly intersect with the main idea line. Sometimes these new thoughts, like tributaries of a river, guide it in a new direction, sometimes they completely change the original concept. And sometimes an idea just dies, which means that either I made a mistake in thinking it was interesting at the time, or I simply grew out of the idea and moved on. It’s a very lively process and I’m extremely fascinated by it, it’s a real creativity.

The portrait collides two personalities on opposite sides of the canvas. The artist knows his task, sometimes already has a preliminary plan of layout, placement of the figure, lighting. But often all this is premature and meaningless. Whoever says he knows in detail what he is going to do, in my opinion, is just lying for solidity. Unlike a craft plan, in which the path from start to finish is clearly mapped out, the artistic let manifest itself in improvisation. It is impossible to plan schemes and poses in isolation from the real person. The original condition for creating a portrait is Personality. Hence the impossibility of planning. When an artist tries to control a Personality as a mannequin, it simply hides inside itself, immersed in its own thoughts. The Personality disappears, replaced by a statue similar to it, with extinguished eyes.

A portrait is an improvisational interaction in which the skill of the artist and the receptivity of the model are fused. The person who is brought to my studio by whim or circumstance has no idea what a mystery and tantalizing mystery they appear before me. Curiosity overflows, and curiosity is essential – otherwise you can’t get close to making a portrait.

I observe the model, trying to see the smallest traits that are specific to the person, that express their true essence. From this observation I formulate a sign, a symbol, an abstract idea that best expresses the image of the model. Then I try to keep this state of the sign in the material, evaluating it step by step and discarding unnecessary things. Weeks, and sometimes months, are spent to achieve the necessary combination of the exact details of the form and at the same time a kind of universal state.

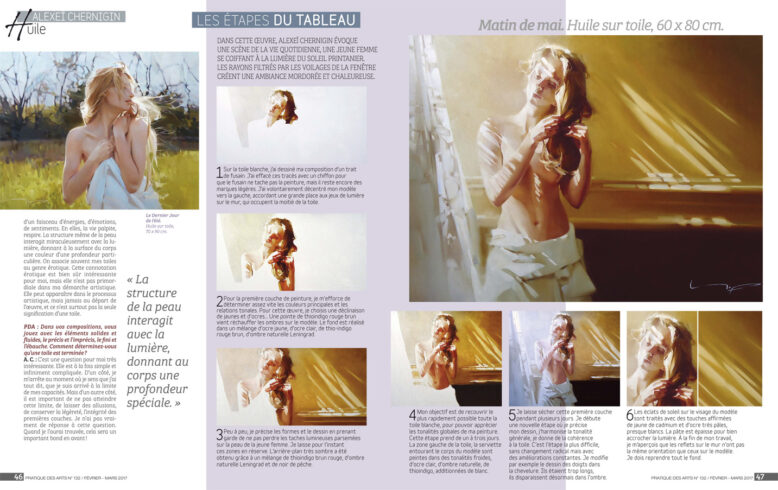

I adore the sun, it gives meaning to everything, fills with emotion. And how many gradations and states it has throughout the day. The sunlight sculpts, it feels the form, it makes the dullest object glow from within. It brings out color, and it also casts everything unimportant into shadow. And reflexes! That’s the essence of painting! Sometimes light is the main character in a painting, when everything else is just the sum of the surfaces you put it on.

For me the woman is a cosmos, an infinite variety of variations and nuances both in plastique, proportions and in the search for new interpretations of the same model. It is not just a frozen form, but a clot of energy, emotions and feelings. Life pulsates in it, it moves, it breathes. The structure of the skin itself interacts with the light in a strange way, giving the surface of the body a special color depth. My paintings often belong to the erotic genre, for me the erotic subtext is of course interesting, but it is not primary in my work. It may appear as I work, but it is never the starting point, or worse, the only meaning.

There are times when a work is over, but over time you begin to feel that it’s spinning inside you again, clinging to the images, setting the flywheel in motion. It means that the idea has the potential for something bigger. So for example I have already had a whole series of works on the theme of carrying the cross. Initially, I tried to understand for myself how a modern icon painted not according to the canon, not on a board and not a monk could look like. I wanted to see the majestic in the simple, ordinary, everyday. To see his face in the crowd, to notice his mournful figure flashing between the rushing streams of cars or freeze, looking at him in the rearview mirror. This is how “Against the Stream” came to be. I wanted above all to emphasize the impossibility of what is happening from our usual point of view. The cars in the picture are positioned in such a way that a collision is bound to happen in the next second. But at the same time we see that so far it has not happened. So either this phenomenon has just occurred, it’s momentary, like a flash… Or on the contrary, this figure is moving in eternity, and all these cars, roads, bridges, exist only here and now. It’s a very personal work and people see it in different ways. I don’t decipher my messages and I don’t give simple answers, everyone is free to find them himself.

An artist’s work now is primarily a search for new meanings, new forms and new horizons. After all, by and large, traditional painting has exhausted itself already in the early twentieth century. Malevich’s black square became her tombstone, the refusal of the further struggle.

Painting began when it was the most informative, profound and essentially the only means of transmitting a visual image, capturing a certain idea. With the emergence of photography, cinema, virtual media, painting is naturally receding into the background in this function. It is difficult for painting to compete with the newest forms of art in terms of the possibilities, the arsenal of means of influence that they have at their disposal. The image in cinema has not only become alive, it is multiplied by the possibilities of combining, superimposing and montage of shots. This is not to mention sound, speech, music, noise, etc. The avalanche of information is pounding down on a person, engaging and subjugating all of his senses.

What can painting contrast to this? The same piece of bleached linen canvas stretched on a wooden stretcher and covered with several layers of glue and gesso. A brush, that stick with a bunch of bristles. Paints, the composition of which was found as early as the 16th century. And a whole system of limitations inherent in the very principle of the flat image. The picture is two-dimensional, limited in size, and, most importantly, naked. Already Plato insisted on the silence of the artist. The peculiarity of painting lies in this double condition: the desire to express and the determination to remain silent. It is a passionate desire to communicate something, but by mute means. This is why painting begins to fulfill its communicative function when the possibilities of language are exhausted and reach their limit: it is like a compressed spring, ready to break through the mute, prompting the knowledge of the inexpressible.

The ease with which we perceive a picture makes us assume that no effort is required of us as viewers to understand it. The suddenness with which, without the slightest effort on our part, a painting presents itself to us paradoxically makes painting the most secretive of all the arts. Painting contains the most important contradiction between the visible, the image, and the hidden, the hidden, the meaning. We should not expect a painting to spontaneously and spontaneously discover its meaning. The fascination of painting is that it is for us an eternal hieroglyph, unresolved and ambiguous. By snatching a fragment from reality, the artist encloses it within a strictly defined framework, but in such a way that the snatched piece acts like an explosion, opening a window to an incomparably larger reality. True painting is the expression of the inexpressible, when the innermost begins to emerge through the ordinary reality, when a face becomes a face, a tree becomes a tree, and a door becomes a gateway.

The language of art is an image, not a direct statement. The artist must say with the picture all that he wants and can, and step aside, leaving the viewer alone with it. He cannot write an explanatory note to the picture or assign an art critic to it. And this is exactly what contemporary art often does, replacing its original meaning of direct and honest contact with some lengthy concepts beautifully explaining what the installation or performance could mean. We live in an era of total substitution of the genuine with cheap surrogates. We watch movies with substituted reality, listen to music through headphones, communicate virtually. Art also strives to fit in; it is becoming more and more technological, gradually moving into the field of design. But design is only aesthetics; it has no spiritual content. That’s probably why I returned from design to painting, to discover something for myself.

In painting there is some inexplicable primordial magic, an inner energy that is like a compressed spring, ready to burst forth, overcoming two-dimensionality, dumbness and all other frames and limits. Perhaps this is why there is a timid hope that the crisis of art that we are all now undoubtedly experiencing will sooner or later be replaced by something new, bigger and real. After all, despite all the funerals and denunciations inflicted on painting in the twentieth century, despite the sharks’ shoals in formalin in the present one, painting is still alive. And not just alive, but as before unfathomable and unexplored for many people. We just have to work harder, both artists and viewers.